古様な素材を提案することで、一番新しいプレミアムラウンジを The Past as the Way to the Future: A Novel Premium Lounge

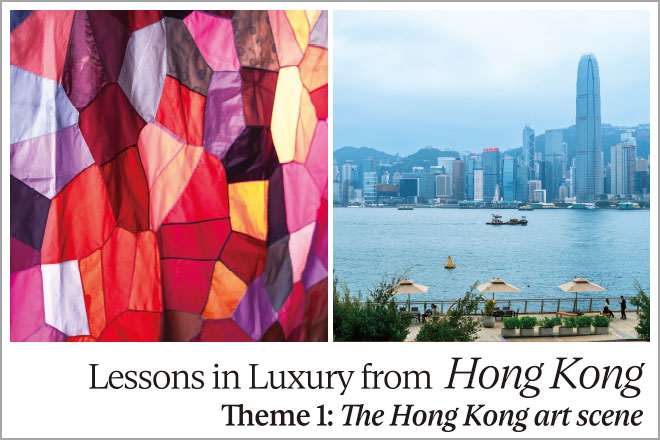

PREMIUM LOUNGE「LOUNGE SIX」

新素材研究所(杉本博司・榊田倫之)

杉本博司と榊田倫之とのユニット「新素材研究所」

榊田:日本には1000年以上の文化のなかで培われてきた素材や工法があるのですが、今の時代に建築の仕事をしていると、どうしてもメンテナンスがしやすいものとか、寿命の長い素材をカタログから選ぶという現代的な手法に、一気に転換されようとしている状況を感じずにはいられません。

そんななかで、2008年に現代美術家の杉本博司と共に立ち上げた「新素材研究所」のコンセプトは「古様な素材を提案することが、今一番新しい」という確信を持って、アイロニカルに新素材研究と言っておきながら、実は古様な素材を研究し提案することを設計理念としています。ただ一方で、単純に数寄屋的や社寺的ということではなく、やはり現代の気分というのがあるので、素材や工法は古来であるけれど、納め方は現代的なディテールで構成していきます。

私は20代の多くを京都の建築家・岸和郎のもとで、近代以降の建築の様式や建築家と社会の関わり、建築家としてあるべき姿勢について学ぶことができました。ですから、建築家としての自分の骨格自体は岸に作ってもらえたと思っています。一方でアーティストでありながら若い頃から古美術商としてのキャリアも経てきた杉本と出会うことによって、日本の文化をエッセンスとして組み込めるようになったわけです。

杉本自身、私と共に新素材研究所を立ち上げるまでは、建築もインテリアも本人が現場に立ち会い、言わばセルフビルドでやってきていました。アート作品同様、そのコンセプトは非常に明解です。ただ、今回のGINZA SIXのように仕事として時間も予算も限りがあるとなったとき、杉本のパートナーとして、彼の主題やアプローチをどう解いて、空間に落としていくか。新素材研究所では、杉本と私がお互いにそんな明確な役割を持って、設計活動に取り組んでいます。

Hiroshi Sugimoto and Tomoyuki Sakakida Join Forces at New Material Research Laboratory

Japan has specific materials and construction techniques that have been cultivated over a millennium, but in this day and age, you can't help but notice that the architectural zeitgeist is shifting towards the contemporary practice of methodically browsing through a catalogue for materials that are as maintenance-free and long-lasting as possible.

Amid this shift, in 2008, artist Hiroshi Sugimoto and I established the New Material Research Laboratory (NMRL) with the philosophy that "The materials of the past provide a breath of fresh air today". So "New Material" is used ironically, as our focus is on researching and imagining novel uses for the materials that were used in ancient and medieval times. But that does not mean our designs are directly based on sukiya-style or the architecture of shrines and temples. We live in a contemporary age, after all, so while our techniques and materials may be from a past age, the design solutions that ultimately result consist of contemporary ideas and details.

I had the privilege of working under the Kyoto-based architect Waro Kishi for most of my twenties, an environment that undoubtedly forged my instincts and my disposition as an architect. Kishi taught me about modern architectural styles, the role of an architect within society, and what an architect ought to be. And then meeting Sugimoto, an artist and someone who has had a distinguished career as a dealer of Japanese antique and folk art, has brought a new dimension to my work and showed me how to incorporate the essence of Japanese culture into what I do.

Sugimoto himself, prior to creating NMRL with me, had already been dabbling in a number of architectural and interior design projects. Like his art work, his designs have a clear concept. With GINZA SIX, however, we were on a timeline and a budget. It was my job as Sugimoto's partner to interpret his themes and approach, and then translate them into interior design. At NMRL, we each have a clearly defined role to play in the projects we take on.

プレミアムラウンジ「LOUNGE SIX」のポイントは「素材」

GINZA SIXでは建築ではなく、プレミアムラウンジである「LOUNGE SIX」のインテリアデザインを手がけていますが、新素材研究所のテーマからぶれずに「日本的なものと現代をどう再編集していけるか」という感覚で空間を解いています。一番のポイントはやはり「素材」に尽きます。

エントランスで顧客の方々を迎えるのは横幅10メートルにもなる、黒漆喰による外壁です。下塗りまでは複数の職人を入れてやるのですが、フィニッシュは熟練の左官職人が一気に仕上げます。黒漆喰はコテの押さえ方によって色のムラが抽象絵画のようになったり、職人の手技を感じてもらえる見せ場になるはずです。

そこから、大正時代に看板建築などに使われたブリキを貼った鉄板の扉を入ったレセプションフロアの床には、1912年から78年まで京都を走っていた市電の下の"電石"を敷きつめました。言ってみればアンティークなのですが、集めていかないと数が揃わないので、「見つけたら、とにかく買う!」。他の建築事務所とスキームが決定的に違うのは、そういうところだと思います。

レセプションエリアの奥にあるメインルームは、開口部の少ない空間で買い物をされた顧客の方々に開放感を感じてもらいたいと思い、自然光が入るようお願いをしました。結果、大きな面にわたる窓には、新素材研究所の特徴的な意匠でもある縦桟(たてざん)の障子を配しています。

また、「LOUNGE SIX」に併設する個室との境は引き戸にして、杉や檜など針葉樹の仲間である鼠子(ネズコ)の木のへぎ板を、胡麻竹(ゴマダケ)で上から押さえたディテールをあしらいました。へぎ板とは木のブロックに刃を入れて目に沿って裂いたものを差しますが、よく茶室の天井などに使われる素材で、今は買う人間がいないので、職人がほとんど残っていません。胡麻竹は茶室のにじり口などに使われる素材です。いずれも日本的なスケールで使われてきた素材を、現代のスケールに合わせて使っています。

LOUNGE SIX, Where the Materials Take Center Stage

For GINZA SIX, we designed not the architecture, but the interior of its premium lounge, LOUNGE SIX, which allowed us to explore a central theme of NMRL: "reimagining Japanese-ness for a modern world". It all comes down to the materials, plain and simple.

Guests will be welcomed at the entrance by a ten-meter wide facade with a kuro-shikkui [black shikkui plaster] finish. Everything up to and including the undercoat plaster was done by multiple craftsmen, but the finishing coat had to be applied at once by a master plasterer. With kuro-shikkui, differences in pressure applied with the trowel create a mottled appearance not unlike abstract painting—this display of craftsmanship at the entrance is the first highlight.

From there, guests enter through a door plated with tin previously used for what they called "signboard architecture" [where traditional wooden townhouses were given a facelift by erecting western-style facades that resembled signboards] and the like during the Taisho Era [1912-1926], and find themselves in the reception area. At their feet is stone flooring comprised of denseki [literally, "tram-stones"] that were originally used to pave the ground beneath the tracks of Kyoto's municipal tram, which operated between 1912 and 1978. These stones are essentially antiques that we had to seek out and buy on the spot in order to put together the number we needed—we have to keep an eye out for this kind of stuff at all times. As I said, our methods and techniques can be unorthodox, but this is what sets us apart from other architectural firms.

Beyond the reception area is the main room, which we designed to let in as much natural light as possible to provide our shopping guests with a sanctuary of sorts, away from the retail floor, which has less natural light in comparison. For the wall-spanning window, we've added one of NMRL's signature designs: a special type of shoji screen with framework composed of vertical bars.

Sliding doors separate LOUNGE SIX from a number of private rooms. We added hegi-ita detailing using thin strips of Japanese arborvitae—an evergreen tree belonging to the conifer family that includes cedar and Japanese cypress—held down with gomadake bamboo. Hegi-ita is made by splitting lumber along the grain using an edged tool, and was traditionally used in the ceilings of tea ceremony rooms and the like, but nowadays there barely exists a market for such a material, and consequently there are only a few craftsmen left who can do this kind of woodworking. Gomadake bamboo is a material that is used mainly for the nijiriguchi [a small, crawl-in entrance to a tea ceremony room]. In both cases we've taken a material used in traditional Japanese proportions and adapted them on a modern scale.

ほとんど特注デザインの家具はユニークさを追求

家具に関しては、ほとんどを特注でデザインさせていただきました。ラグジュアリーなラウンジとなると通常はイタリアの高級家具が置かれていて、シートが深めで、フェザーが入っていて座り心地がいいというパターンなどが少なくないと思うのですが、今回大事にしたかったのはユニークさです。

メインルームに置かれる「ヘリコイドソファ」は、やはり新素材研究所がインテリアと家具を手がけた表参道のカフェ『茶洒 金田中』の「ヘリコイドチェア」がヒントになりました。「ヘリコイドチェア」は、杉本の作品に三次関数の数式を表現した明治期の数理模型と機構モデル群を撮影した写真シリーズがあって、その螺旋(ヘリコイド)を描く模型から関連付けた片肘タイプの椅子です。「ヘリコイドソファ」ではこれをもう少しゆったりとしたサイズで、文字通り、ソファとしてデザインしています。

さらに、2015年に惜しまれながら取り壊されたホテルオークラ東京の本館ロビーにあったテーブルセットもヒントにしました。上から見ると椅子が梅の花びらのように見立てられていたのですが、「ヘリコイドソファ」も丸テーブルとセットになったとき、どこか花のような印象を与えるように意識しています。ただ、現代人のシートハイトに合わせて、足元をスレンダーにしてソファ部分にボリュームを持たせるなど、プロポーションには現代的なエッセンスを入れました。脚の素材には宣徳(セントク)メッキと言って、ふすまの手かけなどに使われる素材を使いました。研究所では古い風合いの色を愛でて"古美色(こびしょく)メッキ"と呼んでいますが、これも職人が少なくなっている技の一つです。

そんな総じて空港にあるようなVIP向けのラウンジとは全く違うアプローチの空間が、顧客の方々の目に新鮮に映ってくれることを願います。

A Unique Arrangement of Custom-Designed Furniture

As for the furniture, we decided to custom design practically all of it. When you picture a luxury lounge, you usually think of luxury Italian furniture, you know, deep-seated sofas with feather-stuffed cushions and so forth. But for GINZA SIX, we wanted to go for a more unique approach.

In the main room are Helicoid Sofas, which are direct cousins of the Helicoid Chairs we designed for the Sahsya Kanetanaka cafe in Omotesando. The Helicoid Chair is a chair with a helix-shaped backrest that takes its inspiration from a series of photographs taken by Sugimoto of "stereometric exemplars", that is, mechanical models and sculptural renderings of mathematical models purchased from the West during the Meiji Era [1868-1912]—specifically, the spiral-shaped "helicoid" sculpture. The Helicoid Sofa is a slightly larger, more inviting lounge chair version of that.

We also took inspiration from the round tables and chairs that graced the main lobby of the regrettably demolished Hotel Okura in Tokyo. When seen from above, the round table and the chairs surrounding it were arranged to resemble a plum blossom in full bloom. Similarly, the round tables and Helicoid Sofas in the GINZA SIX lounge were designed to evoke the image of a flower when arranged together. Of course, we've adjusted the seat heights to accommodate a variety of statures, made the leg area less bulky, made the seat cushions more plush, and gave the overall proportions a modern update. We've applied sentoku plating to the legs—sentoku is a kind of yellow bronze used for fusuma handles [typical fixtures in traditional Japanese-style houses used as sliding doors or room dividers]. At NMRL we affectionately refer to this material and its aged texture as "kobishoku plating" [literally, "beautifully aged color"]. Yet another example of a technique with an ever-dwindling number of master practitioners.

All in all, we've taken a much different approach than your standard airport-style VIP lounge. It is our sincere hope that we have created a novel space for our guests to sit and relax.

(2016年9月インタビュー)

Interview and Text by Yuka Okada / Photographs by Daisuke Akita

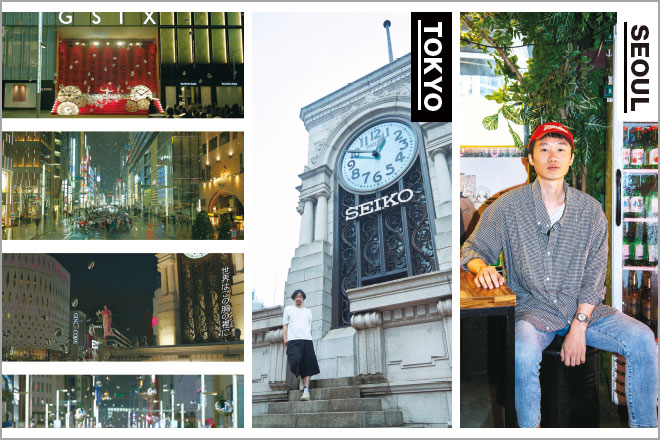

銀座遠望

杉本博司

私の実家は戦前銀座二丁目で創業した銀座美容商事という美容品を扱う問屋を経営していた。戦後は御徒町に移ったが、銀座は子供の頃から慣れ親しんだ街だった。母親とは時々不二家の洋食を食べにいったが、週末は着飾って家族でニュートーキョーの中華料理を食べに行った。ニュートーキョーの窓辺から眺める数寄屋橋下の水面に移るネオンの輝き、今は首都高に覆われその風情は無い。私がアーティストとして頭角を初めて現したのも銀座だった。小学校4年の時、私は銀座松坂屋の屋上から服部時計店方面を見た絵を描き、子供絵画コンクールに出品したのだ。その絵は見事入賞を果たし、世界巡回展に展示され、そのまま帰って来なかった。コンクール授賞式は護国寺近くの講談社本社で開かれ、私は晴れの表彰状を受け取ったのだが、私はその時、その大名庭園風の庭に感銘を受けたのだ。私は大人になったらいつかこんな庭を造ろうと思った。模型少年だった私は、その庭を巨大な自然を模した模型だと思ったのだ。その後私は同じ世界の模型化である写真へと興味の対象を移していくことになる。その庭も首都高6号線となって消えてしまった。こうして私が思いでの地の一画に再びアーティストとして関れるのも不思議な因縁で、私は先祖帰りしたような気分でいる。

銀座は土地柄が美人だ。その地へと赴くとき、人々は着飾って出かけた。美人に厚化粧は向かない。素肌にうっすらとひと刷の白粉(おしろい)。これがこの度のGINZA SIXの化粧方針だ。「New Luxury」とは豪華を隠すことだ、豪華さをひけらかすことが20世紀までの豪華の世界スタンダードだった。しかし我が国の伝統的な価値観ではそれは「野暮」と称されてきた。珠光のいう「名馬を藁屋に繋ぎ止めたる風情」これが「粋」というものだ。粗末な茶室で名椀を使う、というのもこの感性の延長線上にある。しかしここで重要なのは粗末を装いながら実は手の込んだ造作を演出する点にある。いわば金持ちが貧乏人を装う、この美意識は転び様によっては洗練か嫌みの境界線上にある。名人が危うきに遊ぶように、時代の新しい感性は常に反動の揺り戻しに晒される。

銀座の土地柄を美人に保ち続けること、それも日本の伝統的な美意識に則って。これが私達に課せられた使命だ。

Text by Hiroshi Sugimoto

A View over Ginza

Before the war our family home was in Ginza 2-chome where we had a beauty products wholesale business called Ginza Beauty Trading. The business moved to Okachimachi after the war, but I was still very familiar with Ginza from childhood. Now and again my mother took me to Fujiya for Western food, while at the weekend the whole family would get dressed up and go to the New Tokyo for a Chinese meal. The gleaming neon reflections on the water beneath the Sukiyabashi Bridge that I could see from the restaurant's windows are gone now that the canal has been covered over by the Shuto Expressway. It was also in Ginza that I achieved prominence as an artist for the first time. In my fourth year at primary school, I painted a picture looking from the roof of Matsuzakaya department store towards the Hattori watch and jewelry store and entered it into a children's art competition. To my surprise, the picture won a prize, whereupon it was sent off on a world tour—from which it never returned. The prize ceremony was held at the offices of the publisher Kodansha near the Gokokuji Temple. They presented me with a magnificent certificate, but what really impressed me was their formal Japanese garden, which seemed worthy of a feudal lord. "When I grow up, I want to make a garden like this," I thought. As a boy, I loved making models and I saw the garden as a scaled-down model of far larger nature. Later, my interest was to shift to photographs, another "modelized" version of the real world. That garden too has gone, replaced by Route 6 of the Shuto Expressway. By a twist of fate, I find myself once again involved as an artist with a piece of land that is so rich in memory for me. It feels like an atavistic reversion.

As a district, Ginza's character is that of a beautiful woman. Everyone who goes there decks themselves out in their finest clothes. Heavy makeup, however, does not become a true beauty; far better is a light dusting of face powder. GINZA SIX shares this cosmetic philosophy. Concealing luxury is the new luxury. Flaunting it was standard practice worldwide until the end of the twentieth century. According to Japan's traditional values, however, that is mere boorishness. Japanese-style iki, or chic, consists, as Sen no Rikyu said, in "tying a fine horse to a thatched house." Drinking tea from an exquisite bowl in a rustic tea house is an extension of this philosophy. The important thing is to create a pretense of coarse rusticity while deploying the most refined utensils. This esthetic, which is like a rich person trying to pass themselves off as poor, can find itself teetering on a knife-edge between the offensive and the sophisticated. Still, the master practitioners of any art are always drawn to danger and the sensibilities of a new age are invariably exposed to reaction's backlash.

Text by Hiroshi Sugimoto

GINZA SIX ARCHIVE

杉本博司

1948年東京生まれ。1970年渡米、1974年よりニューヨーク在住。徹底的にコンセプトを練り上げ、8 x 10インチの大型カメラで撮影する手法を確立。精緻な技術で表現する作品は世界中の美術館に収蔵。2008年新素材研究所設立。2017年には改装を手がけたMOA美術館(熱海)リニューアル・オープンと小田原文化財団江之浦測候所が竣工。2009年高松宮殿下記念世界文化賞、2010年紫綬褒章、2013年フランス芸術文化勲章オフィシエ、2017年文化功労者など受賞(章)多数。(写真左)

建築家

榊田倫之

1976年滋賀生まれ。2001年京都工芸繊維大学大学院工芸科学研究科博士前期課程修了後、株式会社日本設計入社。2003年榊田倫之建築設計事務所設立。その後3年間、建築家岸和郎の東京オフィスを兼務。2008年建築設計事務所「新素材研究所」を杉本と設立、2013年より同社取締役所長、杉本博司のパートナーアーキテクト。現在、榊田倫之建築設計事務所主宰、京都造形芸術大学非常勤講師。第28回BELCA賞受賞。(写真右)

Hiroshi Sugimoto

Born in Tokyo in 1948. Moved to the United States in 1970. Based in New York since 1974. Established a style based on deeply thought-out concepts photographed with a large-format view camera and 8 x 10 inch black-and-white film. His subtly expressive works feature in the permanent collections of museums worldwide. Founded the New Material Research Laboratory in 2008. Currently responsible for the renovation of the MOA Museum of Art (Atami), and the construction of the Odawara Art Foundation Enoura Observatory, both scheduled for completion in 2017. Has won numerous awards including the Praemium Imperiale (2009), the Medal with Purple Ribbon (2010) and L’Officier des Arts et des Lettres (2013).

Tomoyuki Sakakida

ArchitectBorn in Shiga Prefecture in 1976, Tomoyuki Sakakida studied architecture at Kyoto Institute of Technology and completed his masters at the "Waro Kishi Laboratory" in 2001 before joining Nihon Sekkei, Inc. He established Tomoyuki Sakakida Architect and Associates co.,ltd. in 2003 while also serving as director of architect Waro Kishi’s Tokyo office between 2003-2006, where he headed domestic and international projects for a number of clients including Leica Ginza. In 2008, he established the architectural firm New Material Research Laboratory alongside artist Hiroshi Sugimoto. Currently, he heads Tomoyuki Sakakida Architect and Associates co.,ltd., is partner architect of New Material Research Laboratory, and is a part-time lecturer at Kyoto University of Art and Design.

(2016年9月インタビュー)

Interview and Text by Yuka Okada / Photographs by Daisuke Akita